Antebellum Christmas in Giles County

by Claudia Johnson

Christmas in antebellum Giles County would hardly be recognizable to those accustomed to the present-day commercial Christmas which begins with the after Thanksgiving Day sales and ends with a New Year’s Day headache. Christmas was not a commercial holiday until well into this century, and most of those activities now considered traditional – caroling, trees, cards, Santa Claus – weren’t even known until the Victorian era when centuries old Christmas traditions based mainly in pagan ritual mixed with the mysticism of Catholicism were introduced by immigrants from such places as Germany and Italy.

Southern Middle Tennessee was settled, with very few exceptions, by people of Scotch-Irish and African descent. As to the white population, economic and social conditions had forced their Protestant Scotch ancestors to spend a couple of generations in Ireland before similar circumstances brought their own parents and grandparents to the shores of Virginia and the Carolinas. After the Revolution, these American Scots-Irish accepted land grants as payment for war services or purchased huge parcels of rich Middle Tennessee land and finally, after generations of displacement, found a home in the cane break and the rolling hills of Giles County.

Christmas, then, reflected their heritage. The season did not begin until December 25 itself and ended with Twelfth Night. This custom was practiced in Giles County by descendants of some of the earliest settlers until the 1950s. Festivities consisted of visits, dinners, hunts, and parties in which family and friends thought nothing of traveling long distances by wagon, carriage, or on horseback and spending one or more nights with their hosts. The emphasis was on the visit, not necessarily the holiday. This was a common time for weddings and family reunions since crops were harvested and already at the market and it would be months before spring planting.

Since the Christmas tree wasn’t introduced in America until 1842 by a German tutor, it is unlikely events centered around decorating the tree until those years just prior to the Civil War. Elaborately decorated trees were not known until the later Victorian era, so early decorations were most likely things readily available: strung popcorn and cranberries, baked shaped sugar cookies, pine cones, paper and fabric scrap chains, paper cutouts.

The lack of a tree certainly did not mean homes were undecorated, especially entrance halls, dining rooms and parlors where quests would be received and entertained. Use of various fruits and evergreen garlands was common in the colonies, and Giles County plantation homes would have found hand made cedar and pine garlands entwining the balusters of the staircase, looping over windows and doors, and draped over mirrors and picture frames.

Waxy green magnolia leaves, bright red nandina berries, and aromatic boxwood were used in sprays around candles and lanterns or surrounded serving platters heaped high with boiled country ham and large Chinese bowls filled with hot mulled cider or cranberry juice. Fresh cedar wreathes decorated with okra pods, cotton bolls, holly, or pine cones reflected the Southern influence on Christmas decorating. Shiny red and golden apples where cored and hand dipped candles inserted to light window ledges. Hard to acquire succulent oranges, tangy lemons, and exotic pineapples, adopted in the colonies as a symbol of hospitality, were mingled with apples and nuts gathered on the farm in autumn and freshly cut greenery to create breathtaking, and mostly edible, centerpieces and door decorations. For fragrance, baskets of clove studded oranges were placed near a wood fire under mantelpieces covered with magnolia branches and ivy entwined candles.

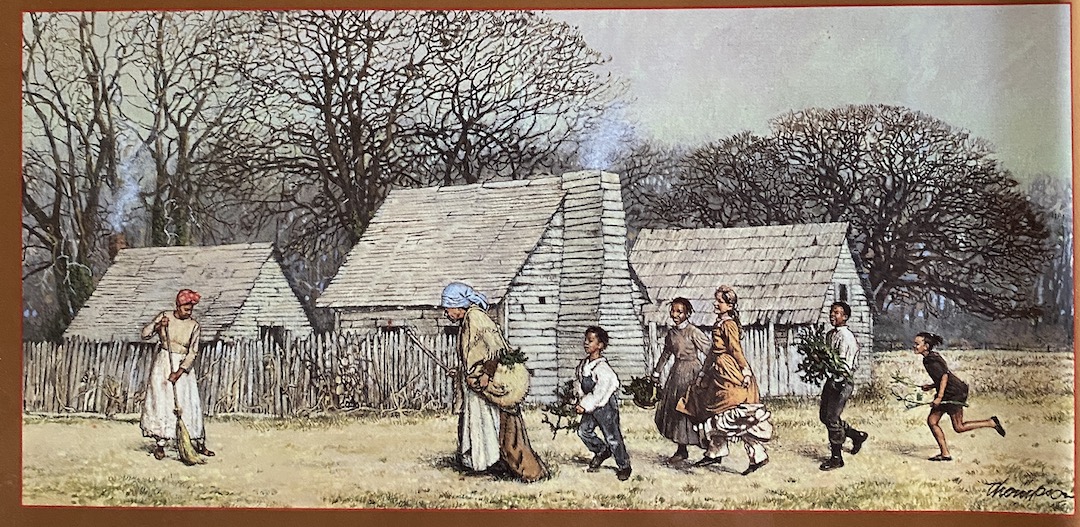

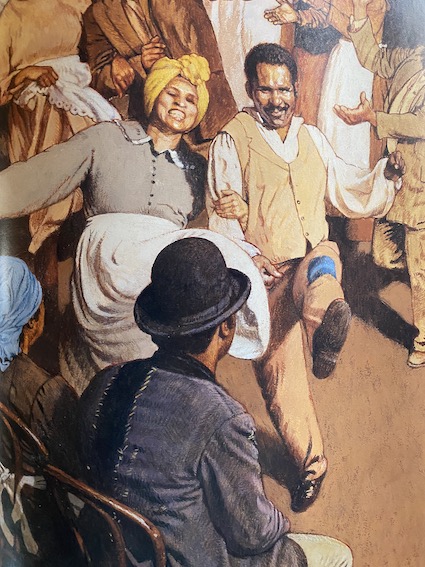

Christmas Day was a holy day with families attending church services or holding their own. Home worship would consist of the eldest male reading Luke’s account of the Nativity, prayers of thanksgiving, and perhaps singing of sacred songs. The only Christmas hymns widely known in America before 1860 were “O Come All Ye Faithful”, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing”, the German song “Silent Night” written in 1818, and “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen”. “I Saw Three Ships A-Sailing” and “Twelve Days of Christmas” were folk songs settlers must have known as well. “Joy to the World” was written in 1848 and soon became popular. Servants were, according to most accounts, given at least part of the day off for their own worship services.

Since the St. Nicholas story was not particularly familiar to Protestant early settlers, Christmas Eve did not find eager and restless children waiting for Santa Claus. The publication of ‘Taws the Night Before Christmas during this pre-Civil War period did not likely impact Southern children until after the war. Only small tokens were given, and those were exchanged on January 6 as their ancestors had done the in the British Isles.

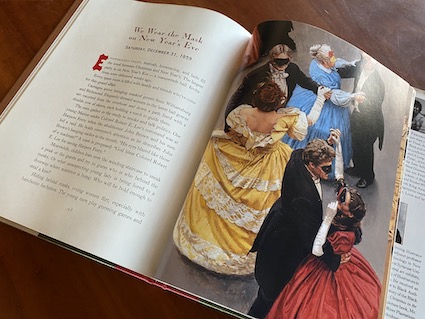

The Christmas season ended on Twelfth Night after a splendid feast of Southern specialties: tomato aspic, meat pies, sweet potatoes, corn pudding, fresh sausage, fruit ambrosia, roasted beef, baked poultry, and wild game. Desserts were served on footed and tiered dishes or epergnes and often acted as part of the decoration. There was marzipan, crystallized ginger, molasses and sugar cookies, plum pudding, teacakes, fruit and jam cakes. All this was topped off with boiled custard, some of which was seasoned for the gentlemen.

The next morning, visitors left, decorations were removed, and the family readied themselves for the cold nights until spring planting.

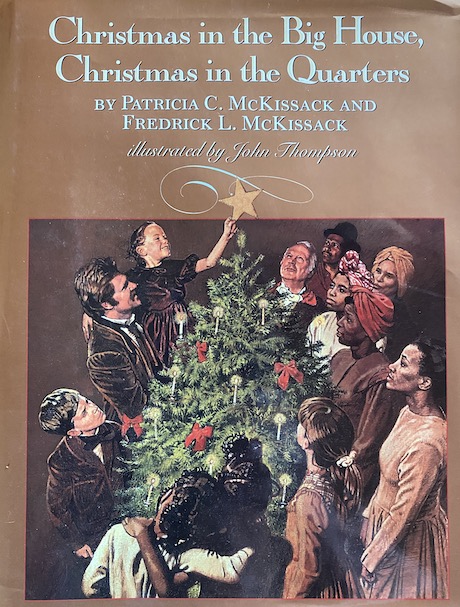

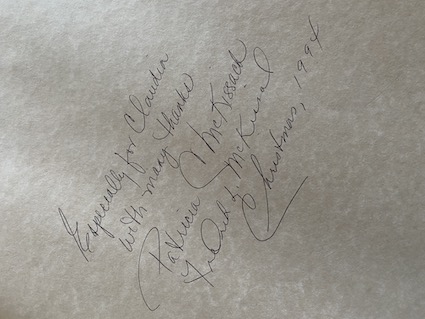

Several years ago when the Gabriel McKissack Marker was dedicated as part of a Tennessee Black History Marker program in North Pulaski, Patricia and Frederick McKissack, internationally known award-winning African-American writers with Giles County connections, came down for a visit. We met in Nashville at the literary festival years before and became friendly. We’d remained in touch over the years, and they asked me how much I knew about Christmas customs in the antebellum South. I did some more research, and later I sent the above story to Pat and Fred. Over the years we became friends, exchanging Christmas cards and phone calls.A while after I completed the research, I took my daughter, Sasha to see them at the Literary Festival in Nashville, but the book they were writing was never mentioned. So I was very surprised to find a package in the mail Christmas of 1994 – a wonderful new book by the McKissacks called Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters. Inside was an acknowledgement page thanking me for my assistance. The book, with its vivid illustrations and beautifully told story, is available for purchase online. Claudia