Benefit of Clergy Does Not Mean What You Think it Does

by Claudia Johnson

Looking back through the Giles County court records, one comes across many cases where a person was convicted of a felony but pled “benefit of clergy” and basically go free.

In the early days of the county, this happened often enough to warrant an explanation. The phrase “benefit of clergy” can still be heard today but usually in association with the birth of a child to parents are not married to each other.

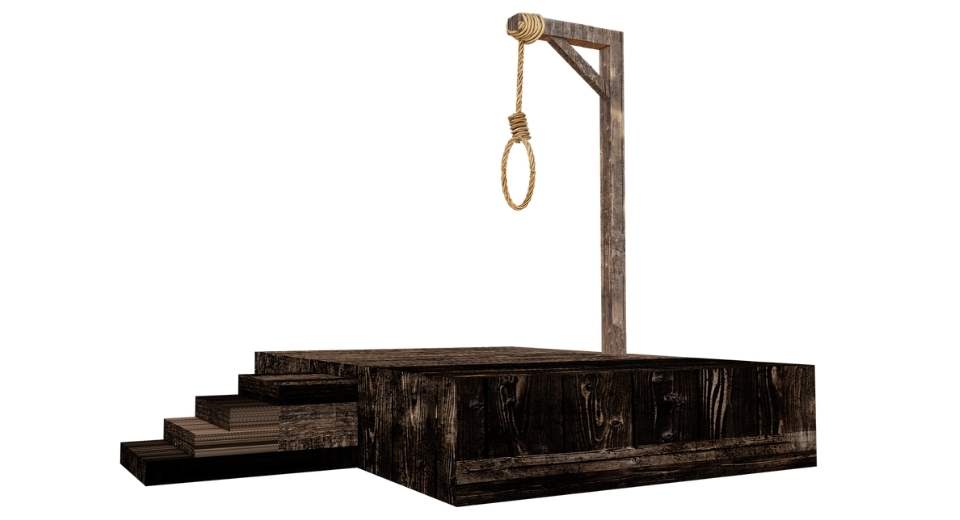

In the 1800s the law was different in many ways from the present. Many laws were simply carried over from ancient English law or Common Law. This meant that hundreds of what are now misdemeanors were then felonies. The punishment for a felony was death by hanging and forfeiture of all the criminal’s worldly goods to the King. This strict and unforgiving method led to the development of a peculiar quirk in the law called “benefit of clergy.”

This developed because a clergyman was not punishable in a conventional manner, but he was turned over to the Bishop’s court, who tended to punish a wrongdoer “spiritually” by working on his conscience in order to show him his wickedness.

In the old days of England no one could read or write except for priests. So, the law presumed that if a person could read, he was a clergyman. When a priest was arraigned in the common court, he “pleaded his clergy”, and either before or after conviction was turned over to the bishop’s court. In later years the priests were simply released, and the Bishop’s officers could arrest him if they so chose.

As civilization progressed, people other than priests learned to read, and this method became a way to soften the cruelty of the criminal law.

Accordingly, if a man were convicted of a felony for the first time, he could claim benefit of clergy, and if he could read, he was not hanged as the law required. He was branded, given a light sentence and released. The branding was not part of the punishment but was for identification since the defendant could claim benefit of clergy only once.

The criminal was branded according to the crime, “M” for murder, “HT” for horse thief and so on. The brand was usually placed between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand. This practice was accepted even after many crimes were punishable by imprisonment instead of hanging. Later the reading test was dropped, and it was commonly accepted that a prisoner had a right to claim benefit of clergy on his first felony offense.

This law was abolished in England in 1827 but existed in Tennessee in its later version. In the 1828 August term of the Giles County Circuit Court case State verses John Erwin, the defendant was brought to Bar for sentencing after being convicted of murder. Erwin pled “benefit of clergy” and was ordered to be branded in the left hand with the letter “M”, sentenced to eight months imprisonment and assessed court costs.

If a man was convicted of several felonies, he claimed benefit of clergy on the first one, and the others were dismissed because under the old law, death by hanging, of course, punished all crimes committed by the criminal.

And this odd interpretation of the law was applied in the 1827 case of State verses Crenshaw, in which the defendant was convicted of horse stealing in Williamson County. He was also indicted for horse stealing in another case and for forgery. Each of these crimes were independent felonies and punishable by penitentiary sentences. At common law Crenshaw would have been hung for all or either. So when convicted on the first crime, the perpetrator pled benefit of clergy. He was ordered to be branded with a “HT” in the brawn of the left thumb, given twenty lashes, jailed six months and was made to stand three times in the pillory on three separate days, two hours each day.

This law grew out of a sort of skewed logic and was looked upon as being logical, so much so that a female couldn’t claim benefit of clergy simply because she couldn’t be a priest. A woman, then, was punished by hanging, or later, imprisonment for the same crime on which a man could claim benefit of clergy.

Also, a man could claim benefit of clergy only once because it replaced hanging, and that, obviously, can only happen once.

This law was abolished in England in 1827 but existed in Tennessee in its later version. In the 1828 August term of the Giles County Circuit Court case State verses John Erwin, the defendant was brought to Bar for sentencing after being convicted of murder. Erwin pled “benefit of clergy” and was ordered to be branded in the left hand with the letter “M”, sentenced to eight months imprisonment and assessed court costs.