James Carrell, War of 1812 Soldier

The history of the Carrell Family is traced from Fairfax, Va., in the early 1700s through Granville County, N.C., during the Revolutionary period on to Williamson County, Tenn., during the War of 1812 and finally to Giles County, Tenn. The family line covered in my free book, Carrell Ancestors, is William Carrell, Spencer Carrell, James Carrell, Mary Carrell Owen, wife of Elijah Owen. For the story of more than 250 years of Carrell/Carroll family in America, including genealogy, documents and more, read my free look at Carrell Ancestors.

by Claudia Johnson

James Carrell was born in Granville County, N. C., around 1787. His birthdate is estimated from information contained in the 1850 Census of Giles County, Tenn. In later years his daughter, Mary Carrell Owen, answered the 1880 Census for Giles County that her father was born in North Carolina.

On March 14, 1813, in Williamson County, Tenn., a James Carrell was brought before the court because he beat and wounded John Roberts. Robert Sammons helped him. James put up bail, but Sammons spent 52 days in jail and was ordered to pay a $13.50 fine.

On Sept. 26, 1813, James Carrell enlisted for service in the War of 1812. His affidavit for 160 acres of Bounty Land stated that he was a substitute for William J. Mayberry, mustering out at Fayetteville, Tenn. He was a member of 2nd Regiment Tennessee Volunteer Infantry, serving under the command of Col. William Pillow. His captain was C.E. McEwen, who later swore upon affidavit that Carrell served under his command.

The regiment to which Carrell belonged was composed of about 400 men who participated in Jackson’s first campaign into Creek territory along with the regiment under Col. Bradley. Both these regiments fought at the Battle of Talladega on Nov. 9, 1813, where Col. Pillow was wounded. An anecdote concerning Pillow at Talladega claimed that Jackson ordered the colonel to fall back once the Creeks attacked, but Pillow refused on the grounds that he would not let his wounded men be “scalped by the demons.” Lt. Col. William Martin, who took over the regiment after Pillow was wounded at Talladega, was later at the center of a dispute with Andrew Jackson over the enlistment terms of the regiment. Basil Berry, who served with Carrell, swore in an affidavit that Carrell was at the Battle of Talladega with him, after which time Carrell was promoted to Major, though there is no official record of this promotion.

The line of march would have taken these men from Fayetteville to Huntsville and on to Fort Strother, where the regiment was stationed after the Battle of Talladega.

Less than 15 miles from Fort Strother lay the Creek village of Tallushatchee, where a large body of Red Sticks had assembled. Jackson ordered Gen. John Coffee, along with a thousand mounted men, to destroy the town. On the morning of Nov. 3, 1813, Coffee approached the village and divided his detachment into two columns: the right composed of cavalry under Col. John Alcorn and the left under the command of Col. Newton Cannon. The columns encircled the town and the companies of Capt. Eli Hammond and Lt. James Patterson went inside the circle to draw the Creeks into the open.

The ruse worked. The Creek warriors charged the right column of Coffee’s brigade, only to retreat to their village where they were forced to make a desperate stand. Coffee’s army overpowered the Creeks and quickly eliminated them. Coffee commented that “the enemy fought with savage fury, and met death with all its horrors, without shrinking or complaining: no one asked to be spared, but fought as long as they could stand or sit.” One of the Tennessee soldiers, the legendary David Crockett, simply said: “We shot them like dogs.” The carnage ended in about thirty minutes. At least 200 Creek warriors (and some women) lay dead, and nearly 100 prisoners, mostly women and children, were taken. American losses amounted to five killed and about 40 wounded.

Shortly after Coffee’s detachment returned to Fort Strother, Jackson received a plea for help from a tribe of allied Creeks at Talladega, who were besieged by a contingency of Red Sticks. Jackson responded to the call by mobilizing an army of 1,200 infantry and 800 cavalry and set out for the Creek fort at Talladega, arriving there in the early morning of Nov. 9. Using the same tactics that had worked at Tallushatchee, Jackson surrounded the town with a brigade of militia under General Isaac Roberts on the left and a brigade of volunteers led by General William Hall on the right. A cavalry detachment, under Colonel Robert Dyer, was held in reserve and an advance unit, led by Colonel William Carroll, was sent in to lure the Red Sticks out into the open. When the Creeks attacked the section of the line held by Roberts’ brigade, the militia retreated allowing hundreds of warriors to escape. The gap was quickly filled by Dyer’s reserves and Roberts’ men soon regained their position. Within 15 minutes the battle was over. At least 300 Creeks perished on the battlefield while American losses amounted to 15 killed and 86 wounded. Jackson marched his troops back to Fort Strother to attend to his wounded and obtain desperately needed supplies.

Prior to the Battle of Talladega, Jackson had expected to rendezvous with an army from East Tennessee under the command of Major Gen. John Cocke. However, jealousy and rivalry between the two divisions of the state prevented the hoped-for junction of the two forces. Cocke, in need of supplies for his own army, felt that joining Jackson would only make the supply situation worse (supply problems plagued the Tennesseans throughout the Creek War). Cocke insisted that his army seek its own “glories in the field.”

James was honorably discharged on Jan. 15, 1814, at Franklin, Tenn.

For the story of more than 250 years of Carrell/Carroll family in America, including genealogy, documents and more, read my free book, Carrell Ancestors, by clicking here.

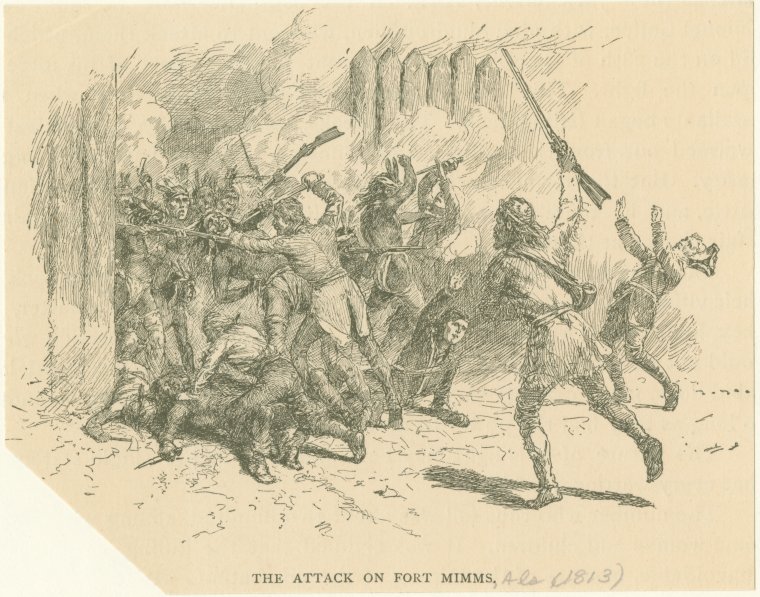

Fort Mims Massacre