by Claudia Johnson

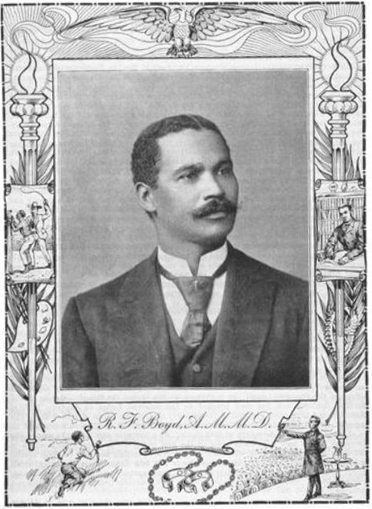

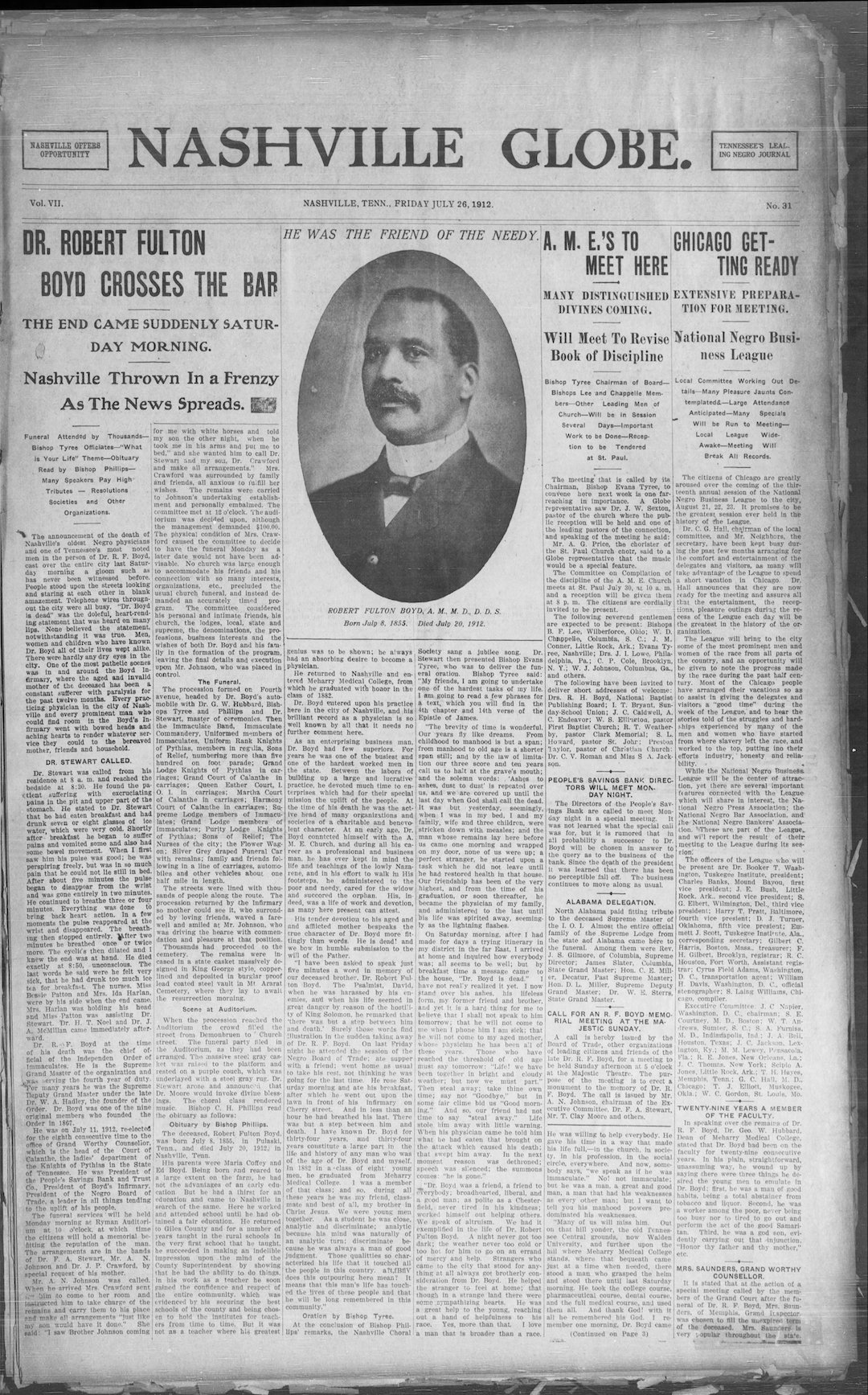

One of the country’s most prestigious African-American physicians, the late Dr. Robert Fulton Boyd, was born a slave on the Solon E. Rose place in Giles County on July 8, 1855.

After working on the plantation throughout his youth, he moved to Nashvill with his mother, who had been absent most of his childhood having been sold from the Rose plantation. In Nashville he worked under one of the most famous doctors and surgeons of his day. Since he could barely read and write, he worked for half the day and went to school the other half, advancing so rapidly that in 1880 he was able to enter the medical department of Central Tennessee College where he received his medical degree in 1882.

After graduating, he began teaching. He obtained a degree in dentistry in 1887 and later earned a degree in pharmacy. He founded the People’s Savings Bank and Trust Company (its descendent became Citizens Bank in Nashville) and was the owner of what was probably the largest black business in Nashville at a time when that city was the third largest in the south.

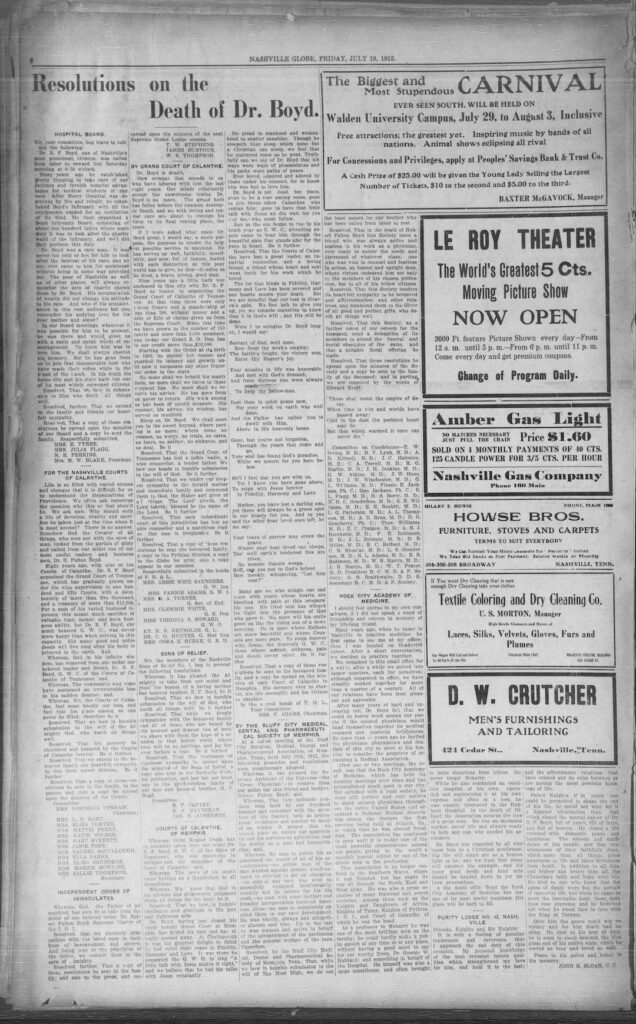

He lead a successful drive to build Hubbard Hospital and founded and was first president of the of the American Association of Colored Physicians and Surgeons (now the National Medical Association) during the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Ga., in 1895.

He was one of the first African-American doctors in Nashville to set up an office for the private practice of medicine, becoming Meharry’s and black medicine’s first successful private practice prototype.He voluntarily scoured Nashville’s jails, flophouses, alleys, old cellars, dilapidated stables and unhygienic sections of the city and to attend derelicts in need of medical attention.

Historians have concluded that such acts, leading to his being named the city’s Jail Physician, along with his opening free clinics for the medically indigent, met a burgeoning city’s critical social and public health needs, filling gaps the white profession chose to ignore.

When Nashville’s City Hospital kicked Meharry’s medical students out in the 1890s because of their race, Boyd expanded his private hospital operations and then made them open for student training. Meharry’s students returned to Metro Nashville General hospital in the same building in 1977.

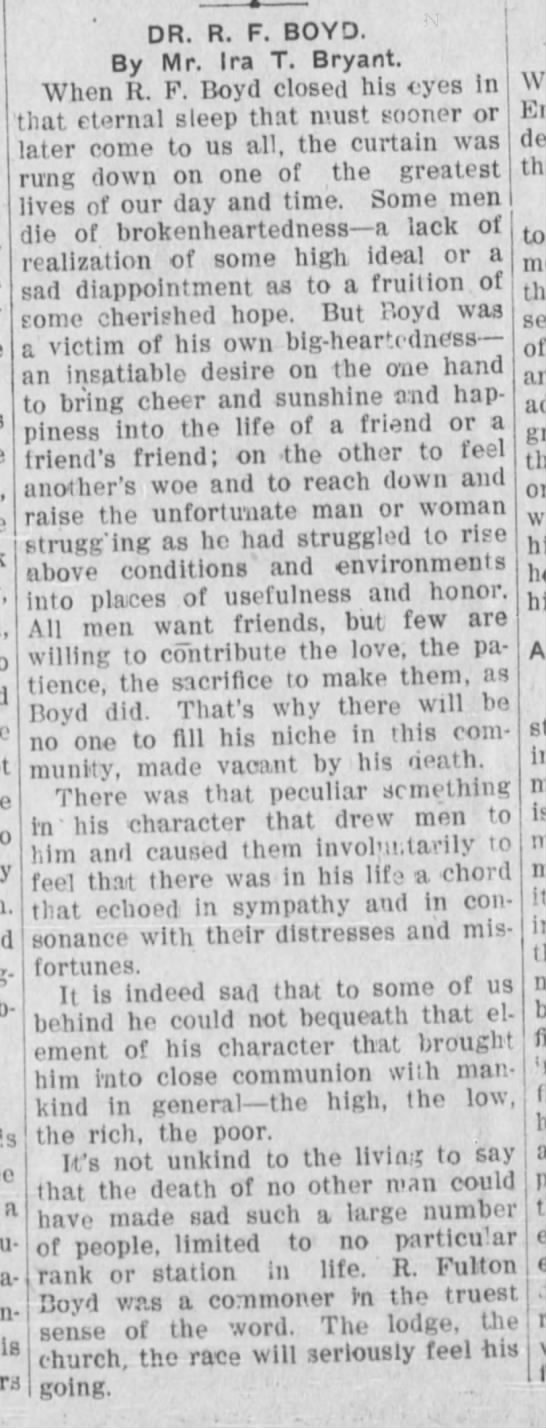

Boyd is credited with leading public opinion instead of yielding to it by constantly upgrading his clinical and surgical skills at medical centers all over the country proving black doctors were not only competent but could be excellent. He established professional ties, and consulted freely, with the finest physicians in Nashville regardless of race.

He is also credited with changing the image of black physicians. Thus, for the first time in the nation’s history, black doctor’s had a niche in America’s health delivery system so they could make a living, even prosper occasionally by practicing medicine.Therefore, at least for Meharry graduates, “sundown doctors” (a disparaging term describing physicians unable to make a living practicing medicine who taught, preached or portered to make ends meet) were soon a memory.

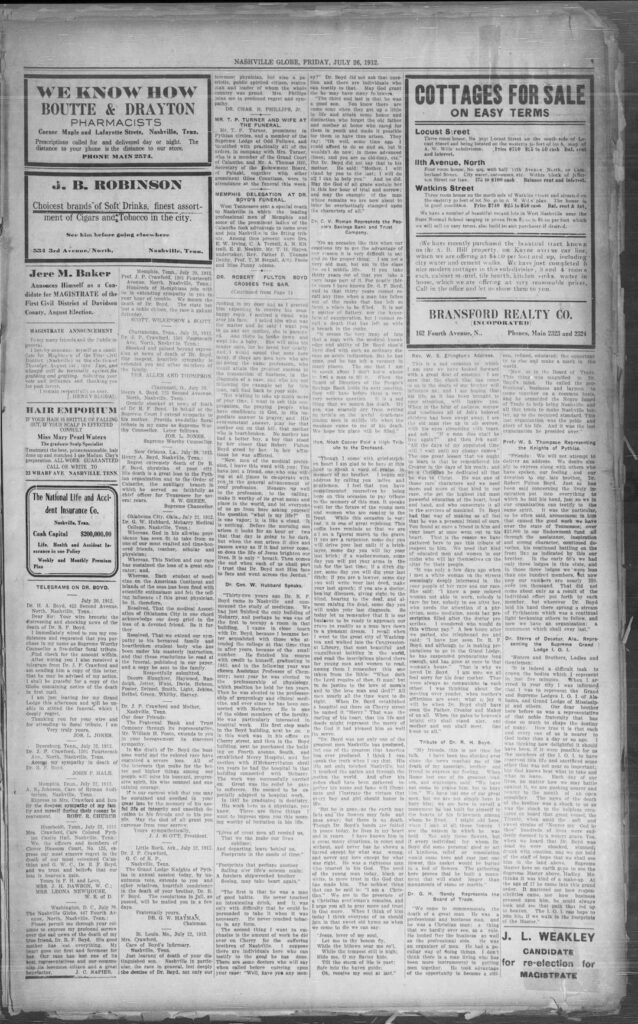

Moreover, the force of Boyd’s personality, reputation and popularity catapulted him into politics, business and leadership positions making him a national celebrity.Strangely, his educational hardships like working for years as a janitor and bricklayer for tuition, being forced to attend night school at Fisk and having to be employed as a part-time teacher during his professional school years burned an intense, almost religious, loyalty and devotion to his schools into his psyche. Supporting the black institutions that trained him would come to dominate, and some historians would say, shortened his life. He died on July 20, 1912, at age 57. He is buried in Mt. Ararat Cemetery in Nashville.